At our last meeting there was a lively discussion about what the increasing social and political pressures on scholarship that uses words like diversity, race, inclusion, and gender might mean for members of our group.

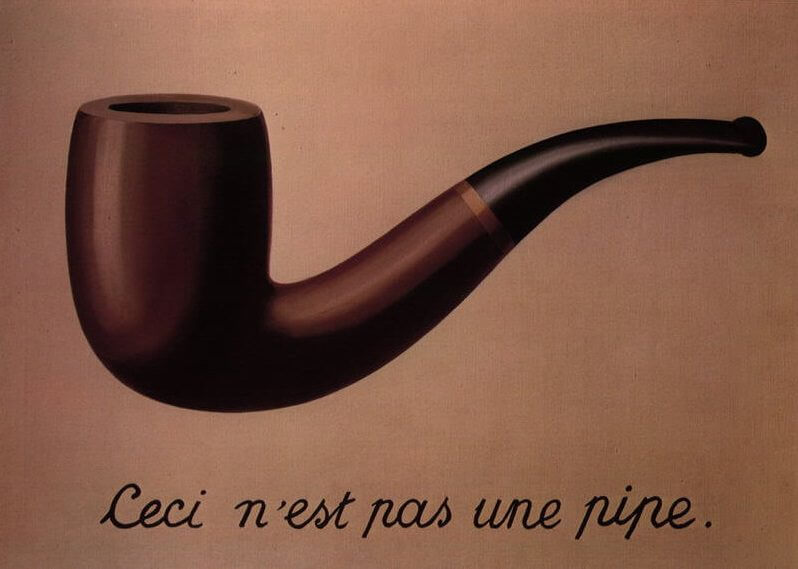

One strategy is to swerve around the words that are being flagged as problematic by using apparently ‘neutral’ language to describe the research we have been doing, and will continue to do, on oppressive systems and practices in higher education. It demands extra work from us, as scholarship and teaching from and about marginalised positions has always done, but that is not going to stop us from saying what is actually happening in the world and our classrooms. There are always time and places in which you have to choose words that will slip by the gatekeepers.

Another strategy is to use even stronger and plainer language. Words like diversity and inclusion are everywhere, but even words like intersectionality and decolonization have arguably been captured by university managers and techniques of bureaucratization. The profusion of committees, charters, guidelines, brochures, and mission statements about the contemporary university’s commitment to various forms of inequality signal some kind of recognition that we need to be talking about these issues. However, research-informed accounts such as Sara Ahmed’s On Being Included, now already 13 years old, note that such work remains largely symbolic, however much energy minoritised scholar-teachers pour into it. In this context, perhaps it would be good to move on from using the words that have already been captured and weakened by university discourse and start talking more directly and plainly about racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, classism, and transphobia. Words like ‘diversity’ or ‘inclusion’ increasingly do the work of obscuring the violent and specific ways university systems and practices actively reproduce inequality.

One of the most interesting strategies is to be even more creative with language, drawing on obscure or culturally specific meanings of existing words to do other kinds of thinking. This is a practice marginalised peoples have always drawn upon to use dominant languages to do their own thinking. Sometimes this has meant reclaiming words used to objectify and humiliate them, using the master’s language to do things the master never dreamed of in his philosophy. And often such deft play with language produces beautiful and profound meditations on human existence through its sheer defiance.

In our discussions at the Critical Pedagogies Project we are always searching for these creative strategies of resistance, what one participant in the last meeting described as the capoeira of pedagogy. We invite you to share your ideas about the language we could use to continue doing the work that matters to us — whether you want to make a case for coining new words, reclaiming old ones, or bringing culturally specific uses of words to a larger community, let us know how we could dance with you.